It is the oldest house in Tiaong, but long abandoned and decaying

from disuse, a relic historied with elements of a colonial past and

a war-time occupation by the Japanese, rebuilt from the damage wrought

by the bombardment during the American liberation. Now it stands,

a dying landmark, prey to vandals and petty thieves stripping it of

wires, doors and metal scraps, lovers seeking a trysting place, treasure

hunters still in search of Japanese caches of treasures.

The imposing stone structure with the central

garden sculpture built in 1927, is a testament of the efforts and

conceptions of two men: Isidro Herrera and an architect of great renown

in his time, Tomas Mapua.

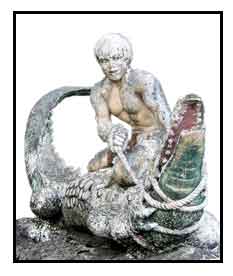

The garden sculpture of Elias - in the middle

of the horseshoe-shaped pool - was inspired and drawn from Jose Rizal's

El Filibusterismo. The sculpture of the half-naked Elias, in his brawn

and bravado, subduing the crocodile, holds frozen in time the smoldering

rage of the filibusters against the Spanish dictatorship.

Alas, for some, the crocodile has also stood as

a symbol of the bourgeosie's cruel greed, and Elias, the common man

that takes up the struggle against the collective burgis.

HISTORICAL

NOTE: The house was built in 1927 to Thomas Mapua's architectural

design. The back part of the house was damaged by the bombings at

the end of the Japanese occupation; repairs and additions were done

in 1950 by C. Gonzales, a Candelaria architect. The facade persists

of Thomas Mapua's original architectural design, including the Elias

sculpture and the garden's other concrete structures.

The Ghosts Within

Many say it's haunted. Headless

soldiers in Japanese uniforms, helmets in hand. An elderly couple

in regal white slowly descending the circular steps, completing the

descent as a headless apparition. The rattling of doorknobs. Doors

that suddenly refuse to open. The sound of shackled walking and the

dragging of chains. The heavy cold air that wraps around the intruding

guests.

Many have

tried to brave through a night. My brother's karate group, brown and

black belters, visiting for a weekend of instructions and exhibition

of their martial art skills. Another, a nephew and his barkada,

aware of the ghosts, intent to tease and draw them out of their ethereal

habitats, their nerves augmented by alcohol and fraternity. None lasted

to the midnight hour, skedaddling back to Manila, their machismo bruised

and tempered.

Some believe

the spirits have claimed the space and have joined together to hinder

and stall all efforts to sell or demolish it.

Recent

caretakers continue to tell of an old lady in the traditional ghostly

garb of white, her white hair loose on her shoulders, lingering around

the rooms, with a penchant for conversing with their little children,

bringing them to giggles and laughter.

Its hauntedness

is kept alive by the townfolk – stories from the diminishing

number of old-timers who remember the olden days and a constant replenishing

source of sightings from passers-by as they steal glances at the framed

glass windows and doors sometimes catching shadowy forms moving about

– stories that resuscitate as the October days march into Halloween

night.

Some of us still suffer a connection with

it, a common bond with a shared past, hoping, searching for a

way to save it. And I, one of them. I was born in that house,

haunting me with memories of the halcyon days of a childhood

wrapped in trimmings of provincial gentry, fondly remembered,

not for its previleges, but for the wonderful windows that opened,

that took us to ricelands, the coconut plantations, the hills

and rivers of rural Tiaong, the warmth of its people, the color

of their endless stories and mythologies. . . and inevitably,

the reason to come back.

Yes. . . the old house, i visit it frequently. It

has been stripped empty; the rooms now open, mere joists and beams.

Still, easily, when I close my eyes, the sounds of a bygone past engulf

and sometimes, a cold air gently embraces me. Yes, that old stone

house, it is both that. Haunted. . . and haunting.