To

the hardy-drinking rural folk, lambanog, the coconut liquor, is "THE" Philippine

alcoholic beverage – the arrack of the masa.

Primarily produced

in the Southern Tagalog region, particularly the Quezon area, lambanog

has been called the "coconut nectar," 100% natural, 80-95

proof spirit that originates from the sap of the unopened flower

of the coconut. It has slowly flowed into alcohol's tributaries of tastes,

meriting comparisons with the other spirits of international renown,

earning attributions like "Philippine tequila," "coconut vodka,"

"coconut wine," and "Philippine grappa," and starting to appear

in high-end bar menus of martinis and mixed drinks, laced with guava

juice or passion fruit.

Misnomers

It's not wine, vodka, grappa, or tequila.

What's in a name? To most, it's lambanog. To lambanophiles and urban-bibbers, lamba.

Technically, it is palm liquor, which is more inclusive. Besides coconut, lambanog is also produced from the sap of nipa palm's fruit (sasa).

Generically, some refer to it as a Philippine arrack. "Arrack"-an alcoholic liquor distilled from the sap of coconut palm or from rice. But "arrack" might sound like a Japanese phonetic bastardization of "alak" - the generic local word for alcohol.

Coconut nectar might pass, albeit rather too burgis or too English for a masa drink.

The rest are simply misnomers: Philippine vodka (Russian rooted alcoholic spirit made from distillation of rye, wheat, or potatoes), Philippine tequila (Mexican liquor made from agave), Philippine grappa (brandy distilled from the fermented residue of grapes after being pressed in wine making), Philippine wine (alcoholic drink made from fermented juice of fruits and plants (grape juice, tuba, dandelion wine, bignay wine).

|

|

The traditional production process

starts, perilously, high up above ground. Much of local production is third-world crude,

and although the distillery equipment and set up may differ depending

on budget and production volume, much remain the same.

(1) The clusters of coconut trees are connected by a system of

bamboo poles – one to walk on and another as handrail

to hold on to and hang and push the hand tools through. (2)

The sap is collected by the mangkakarit (mangangarit), 30 or more feet

up in the air, perilously walking from tree-to-tree. (3) His tools of trade: The cutting tools (panghawan and pangkarit)

ensheathed in the wooden "gatok" and the stainless steel collecting

container (batang). (4-5) The "heart"

of the coconut (white arrow), the source of the sap, is slit (pungos)

and bled of its sap (tuba) which drips into collecting bamboo receptacles

(tukil) to which it is attached. A single mangkakarit can manage the

cutting, bleeding and sap collection from 100-120 trees a day.

(6) When the sap collected

from the bamboo receptacles has filled up the mangkakarit's batang,

it is transferred to a 5-gallon pail (the produce of 4 coconut trees),

and lowered by rope and taken by a helper (taga-tangal) to the nearby distillation area. (7) The toddy-filled

pails are emptied into 32-gallon containers where it goes through fermentation,

becoming "tuba," optimally not more than 2 to 3 days, to avoid unwanted acidity. (A 32-gallon

drum of sap yields about 6 gallons of lambanog.) (8) After fermentation, the "tuba" toddy is skimmed of its upper

layer of floating impurities –butterflies, insects and forest litter –

and emptied into a stainless steel drum for distillation, its 64-gallon

capacity to yield about 12 gallons of lambanog. (9) The cooking fire is provided by the burning of coconut husks and leaf

ribs, old bamboo and discards of wood scraps, closely monitored and

controlled, lest the toddy burns and produces a dark and unpleasant

tasting distillate. It is a temperature-critical process; over-boiling

is avoided, and the longer the distillation time, the finer the distillate.

The final distilled spirit ranges from 80-95 proof; some consider 80-proof

ideal. (10) Distillation proceeds with

the vapors cooling through a system of coils submerged in a vat of water. (11) The distillate drips out and passes

through a crude and third-worldly filtering system and into a collecting

receptacle. The first ten ounces or so is a highly concentrated

methanol-toxic distillate referred to as "bating," sometimes included with the total distilled product. Some distillers set it aside for sundry

uses by local healers, especially for therapeutic massage or in small doses for

menstrual irregularities. Some use it for spiking low-proof or low quality

lambanog. The end part of the distillation is called tails

or parasan. Tails are higher boiling components, with higher amounts of fuel oils

and acetic acid, recognized by sight (loss of the fine bubbles), taste (loss of sweetness, sourness) and smell (blunting of the aroma). Usually discarded, some unscrupulous distillers use the parasan to increase production volume, producing an inferior end product. (12) In 6 to 8 hours – Voila! – crystal clear, 80-

95-proof, 100% natural lambanog!

In

rural Quezon, it was once considered at the low-end of the alcohol preference

– the alak of the peasantry, the arrack of the masa.

Not anymore. Affordable at P 160 to 200 per gallon ( P140 to P150 per gallon at volume purchase), It is now the preferred alcoholic drink – over gin

and beer, that is, if it can be found pure and unadulterated.

Unfortunately, much of the rural-provincial consumption access is through unlabeled

recycled plastic gallon jugs sold from roadside shoulder-stalls and

stores; alas, often chemically adulterated.

| Diluents and Adulterants |

|

100 % pure and natural lambanog can be a nectarous delight, first assaulting with a 80-95 proof buccal rousing of the taste buds then receding to a sweetness at the tip of the sip. Alas, this is not the common lambanog experience. Commercially bottled lambanog lacks of the subtle nuances. Roadside lambanog is likely adulterated.

Rural

consumption of lambanog has suffered recurrent periods of disfavor

from local grapevine news of illnesses caused by the drinking of

"bad batches." Some producers sadly confess that much

of what they produce, once purchased for local commerce, suffers dilution

and adulteration with chemicals and a miscellany of extenders. Much of the roadside purchases, in half-gallon or gallon recycled plastic or bottle jugs is second-rate, washed down, extended and chemically adulterated toddy of such inferior quality easily discerned even by non-lamba-connoisseurs.

The ways of adulteration are many – well kept secrets of the rural underworld. An often suspected process is the use of the parasan (tails). Usually discarded, it is mixed with sugar cane fino and added to 2 gallons of boiled water, and then added to dilute 8 gallons of lambanog.

So, buyers beware. For true 80-95 proof 100% natural lambanog, your best bet is to suffer a search for a trustworthy source or a distillery in the coconut hinterland.

|

|

Testing for Purity

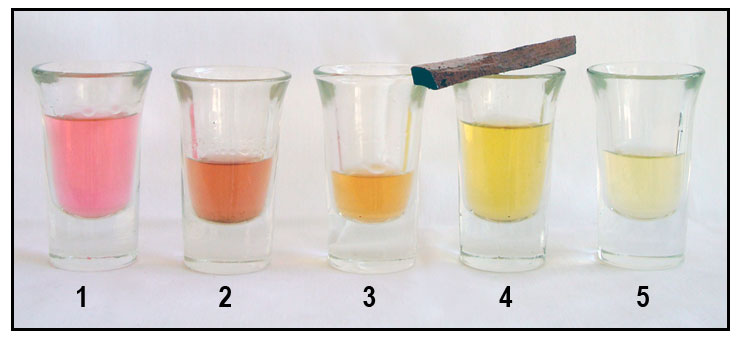

The traditional litmus test for lambanog purity in the Tiaong area uses a strip of sapan wood. Stirring it in the test jigger imparts a yellow color for unadulterated lambanog and a pinkish or reddish color for adulterated batches. (See below)

|

|

|

| |

|

| Lambatonic |

|

• 1 glass of buko juice (chilled)

• 1 or 2 shots of lambanog

• Squeeze of kalamansi

• Honey or sugar to taste (optional)

Lambatonic 2

• Equal amounts of pure kalamansi juice and lambanog.

• Honey to preferred sweetness.

|

|

Silibanog

Bicol Express

• Drop 6-12 whole chili peppers (siling labuyo) in a liter of lambanog.

• After 4-6 weeks (or sooner), test and dilute with regular lambanog to your degree of fiery preference. An acceptable proportion is one measure of chili'ed lambanog to 8 measures of regular lambanog.

• Undiluted, you'll be drinking something that qualifies as verifiable Bicol Express.

Pulang Lupa Lamba Punch

•Ingredients: Lambanog, orange juice, pineapple juice, nata de coco, and lychees

• One measure of Lambanog for every five measures each of orange juice and pineapple juice. (Increase the measures of Lamba according to taste.)

• Add whole lychees and cubes and juice of nata de coco.

• Optional: sprite

|

|

| |

|

Other Uses

It's Not Just a Great Drink

1. Used for making medicinal plant tinctures.

2. Great for cleaning glass and metal.

3. Efficient for cleaning molds and grime from wood.

4. Lambanog flavored with raisins or various fruits and raisins can be used for glazing or soaking holiday cakes. A great Pinoy alternative to "rum cakes.

5. Some healers use the "bating" for therapeutic massage or prescribe it for menstrual irregularities.

|

|

| |

|

| Commercially Bottled Lambanog |

|

Of the commercially bottled lambanog, Mallari Distillery markets a good one. Although relatively expensive, at P 250-350 for the 375 cc bottle, it's a great try-me size, for giving away, for packing a few in your check-in luggage.

|

|

THE

FRUITS, FLAVORS, FRINGE AND THE FLAMBE THE

FRUITS, FLAVORS, FRINGE AND THE FLAMBE

Au

naturel, true unadulterated lambanog can tickle and surprise many a

discerning palate with its nectarous essence – a delicate sweetness that lingers after the sip or swig.

Some prefer it aged; some, aged and flavored with the sweet essences of native fruits.

Aging

the nectar is an endeavor of the lambanophile, the rare lambanog

aficionado, investing both time and passion for the reward of

something uniquely and delectably Pinoy.

Clear and colorless,

colorants are often used in the aging process. Sappan wood imparts a

yellowish color and a mild peculiar flavor. (See:

Sapan) For short-term flavoring,

strawberries provide both taste and a pinkish coloration within two weeks. Raisins, easily

available, provide sweetness and the familiar reddish brown color. Jackfruit

(langka) is believed by some to augment the alcohol's intoxicating ability.

Depending on the budget, aging and flavoring may be done with a mixture of fruits

that are in season – grapes, raisins, langka, chico, dried mangos,

and mangosteen, sealed and buried a meter deep in the ground or cellared

in the cool and constant climate of Baguio for one to five years. Although

the fruits cause a dilution and diminution in the alcohol-proof, each

year of aging imparts a discernible enhancement of the taste. A five-year

aged-and-fruited lambanog has wow'ed enough tasters into calling it

brandy- or liquer-quality, and alas, often suffering the caveat - with the alcohol content deceptively fruited and masked, a few yummy-hurried jiggerfuls

will bring about a surprising buzz, much sooner than later.

Some of my recent experiments with flavoring have yielded surprising results. Dried figs from California, after a mere month of soaking, gave a surprising and pleasing flavor of figs. Whole chili peppers (siling labuyo) in varying amounts, after a month, imparted varying degrees of hotness, from Bicol-Express fire-breathing capsicum-fieriness to a civilized and chili-subtle spicy-tingly buccal warmth at the sip's end. A singular taste deserving of a variant name: Silibanog. Some of my recent experiments with flavoring have yielded surprising results. Dried figs from California, after a mere month of soaking, gave a surprising and pleasing flavor of figs. Whole chili peppers (siling labuyo) in varying amounts, after a month, imparted varying degrees of hotness, from Bicol-Express fire-breathing capsicum-fieriness to a civilized and chili-subtle spicy-tingly buccal warmth at the sip's end. A singular taste deserving of a variant name: Silibanog.

Lambanog is finding its way in an increasing number of mixed drinks and has proven itself a great liquor to use as a base and providing a native edge to a variety of concoctions. The addition of a variety of schnapps - peppermint, peach or pear - takes the coconut liqueur to a palate-teasing variety of mixed-drinks. The Kahlua™ liqueur imparts a nice coffee flavor, and equal parts of Kahlua and lamba make a nice after-dinner coffee drink. A more affordable rural concoction is a mixture of lamba and Nescafe™. In Tiaong, "gising-gising" contributes a communal punch concoction for festive occasions – 2 gallons of lambanog with a bottle of Fundador™ brandy, plus a liter or two of apple juice. Lambatonic – a mixture of buko juice and lambanog with a squirt of kalamansi – is a true rural contribution to a short list of Filipino mixed drinks.

Fringe users, steeped in myth

and superstition, have been known to put a snake or a fetal abortus in the jug of

lambanog, with written prayers (orasyons) on small strips of paper

rolled and sealed in plastic, believing these will lace their daily jiggers with health and

empowering benefits.

The

occasional macho-comic relief performance in an evening of rural bacchanalia

is the lambanog

flambé -- a jiggerful of the nectar aflame in blue, quaffed down

to great delight and applause, for the few and fleeting moments of a

100%-natural fire-eating spectacle.

| For Filipino

food – sweet and salty, sour and saucy, spicy and savory –

this coconut nectar makes a great aperitif and the fruit-aged and flavored lambanog, a great cordial. |

|

Lambanog is the essential rural

celebratory drink, laced with protocol and ritual. It is an unusual

town or barangay festivity that will not find it in the feasting table.

In some parts of Quezon, women keep pace with men, jigger-for-jigger

(tagay-for-tagay). Usually, a single jigger is used. The first jigger

is often toasted to someone's memory and doused on the ground before

being passed around the circle of drinkers. The jiggerful is usually

taken in a single swig, the glass turned to the ground or over the shoulders

to empty it of the last residual drops before passing it on. The swig

is followed by a nibble of the pulutan (side dish) from a centered plate

using a single shared spoon or fork. . .um. . . quite the unhealthy

rural custom. As is common in the macho ways of rural drinking, the

jigger goes round-and-round-and-round, as the decibel of simultaneous

story-telling increases. . . . . and not unusually, until only one man

remains, or a waiting wife, akimbo, stares the evil eye, or the last

gallon-jug has emptied.

The Sapan Wood Test

Testing for Purity |

|

| The Traditional Rural Litmus Test: In rural Quezon, the sapan wood has long been used for testing the purity of lambanog. A strip of sappan wood swirled in unadulterated lambanog will impart a yellow color. Above: (1) Gin, bright pink. (2) Vodka, reddish-brown. (3) Bating, the initial distillate in the lambanog process gives a deeper yellow-orange color. (4) Coconut lambanog with the typical "true" unadulterated yellow coloration (5) Nipa or sasa lambanog with a lighter yellow, probably due to a lower "proof." |

The intrepid

traveler should try this Philippine nectar. . . someplace upscale in

Manila, where it is making appearances in high-end bar menus as a mixed

drink, martini, or laced with guava juice or passion fruit. Or in the hinterlands, minus

the ritual and pulutan sharing.

Unfortunately, although commercially bottled lambanog has gained inroads in the urban-suburban and export markets with their preppy packaging, colorfully labeled and fancifully shaped bottles, most are a far cry from the all-natural original. One that passes muster is the lambanog produced by Mallari Distillery, albeit, a little expensive.

Lambanog peddled in stalls along the provincial roadside is always suspect for extenders and chemical

additives, and the further away from the Quezon-Batangas area, the more

likely it is diluted and adulterated. In fact, I have never seen a roadside-purchased lambanog pass the "Sapan Wood Test." Unless severely budget-constrained or desperate to be soused, roadside lambanog is not worth a try.

For true 80-95-proof 100% natural lambanog,

it's best to search out a trustworthy source or purchase on-site from

one of the distilleries scattered in the coconut hinterlands.

Better still. . . pass

by the White House in Pulang Lupa for a jiggerful swig of "certified"

pure nectar lambanog, 90-95 proof, 100% natural. |